- Carbon Finance

- Posts

- 🎨 Adobe: Priced for Extinction

🎨 Adobe: Priced for Extinction

Investment Research Report: Adobe

📅 Publication Date: 2/22/2026

Investing is a game of conviction, and conviction is built on clarity. My research is an attempt to distill my thoughts, challenge my assumptions, and refine my decision-making. It is not a display of expertise, but a foundation, one that will evolve over time. My goal is simple: to become a sharper, more disciplined investor. If you take away even a single insight from this, then it has served its purpose. Feedback is always welcome. After all, the best investors never stop learning.

Note: This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice; please refer to the full disclaimer at the end.

1. Investment Thesis in One Sentence

Adobe is valued as if structural decline were inevitable, yet steady mid-single-digit growth would be sufficient to generate asymmetric upside.

2. Introduction & Brief History

Source: Adobe

Adobe was founded in 1982 by John Warnock and Charles Geschke with a simple but powerful idea: digital documents should look the same everywhere. That insight led to PostScript and later PDF, which became the global standard for digital document exchange.

Over the following decades, Adobe expanded into creative software, with products like Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, and Premiere becoming industry standards across design, photography, and video. By the late 2000s, Adobe had effectively won the desktop creative software market.

The next major inflection came in 2013, when Adobe fully transitioned its Creative Suite to a subscription-based model under Creative Cloud. The move was heavily criticized at the time, but it transformed Adobe from a cyclical software vendor into a recurring-revenue platform with far greater scale and predictability.

Adobe’s Creative Cloud, Source: CapCut

Adobe later ventured into Digital Experience, expanding beyond creation tools into analytics, marketing automation, personalization, and customer data, and repositioning itself as a broader enterprise platform embedded across digital commerce and marketing workflows.

Entering the 2020s, Adobe was widely viewed as one of the highest-quality software businesses in the market, supported by strong margins, durable free cash flow, deep customer lock-in, and the belief that it controlled the core layers of creative and digital workflows.

For the first time, that perception is being challenged. The emergence of generative AI has altered how content is created at the entry level while raising more fundamental questions about the long-term economics of the business.

The question now is simple:

Is AI sending Adobe to its deathbed, or is the market overreacting?

3. Business Overview

Adobe is a global software company offering products and services that enable individuals, teams, and enterprises to create, publish, and manage digital content, while also helping businesses design, execute, measure, and optimize customer experiences across analytics, marketing, and commerce.

Historically, Adobe reported its business through three core segments:

Digital Media, which encompasses creative and document tools, including Creative Cloud applications such as Photoshop, Illustrator, Premiere Pro, and Firefly, as well as Document Cloud products like Acrobat and Adobe Sign.

Digital Experience, which focuses on enterprise customer experience software, including Adobe Experience Platform, Adobe Analytics, and related marketing, personalization, and data solutions.

Publishing and Advertising, which consists primarily of legacy products and niche offerings and has become increasingly minute over time.

More recently, Adobe has adjusted how it frames its business. Rather than organizing exclusively around product lines, Adobe now emphasizes customer groups:

Business Professionals and Consumers, which includes individual users and smaller businesses with lighter-weight creation, document, and productivity needs.

Creative and Marketing Professionals, which includes professional creators, agencies, and enterprise marketing teams embedded in high-end creative and customer experience workflows.

From fiscal year 2026 onward, Adobe will focus its official financial reporting and guidance on these two primary customer-facing segments, while continuing to provide the traditional segments as supplemental disclosures. Throughout this analysis, I will reference both frameworks where relevant.

Company-Level Summary:

Adobe has delivered highly consistent revenue growth over the past decade. Total revenue has compounded at approximately 17% annually over the last 10 years. As the business has scaled, growth has naturally moderated, slowing to roughly 13% over the past five years and 11% over the past three years. Despite this deceleration, Adobe continues to grow at a double-digit rate.

Digital Media accounts for roughly 75% of total revenue, with Digital Experience contributing the remaining 25%. While Digital Media outpaced Digital Experience over longer historical periods, growth rates have converged more recently, with both segments growing at similar low-teens rates over the past five years.

The Americas account for nearly 60% of total revenue, with the U.S. representing 93% of that total. EMEA contributes roughly 25%, while Asia-Pacific represents just under 15%. Growth has been relatively consistent across regions, which points to Adobe not being dependent on any single geography for expansion. That said, the U.S. is still its most important market by far.

Net income has not followed the same smooth trajectory as revenue. Between 2020 and 2024, profitability was largely flat, driven by a rise in operating expenses and an acquisition termination fee. However, in the most recent fiscal year, Adobe reached record profitability, with net income surpassing $7B.

Free cash flow trends broadly mirror net income and were relatively flat between 2021 and 2023 before re-accelerating. In the most recent year, Adobe generated approximately $8B in free cash flow, reinforcing its position as a consistently cash-generative business.

4. Context

As seen in the previous section, Adobe continues to grow. Revenue remains on an upward trajectory, its core businesses are still scaling, geographic performance is broadly consistent, and both profitability and free cash flow are near record levels.

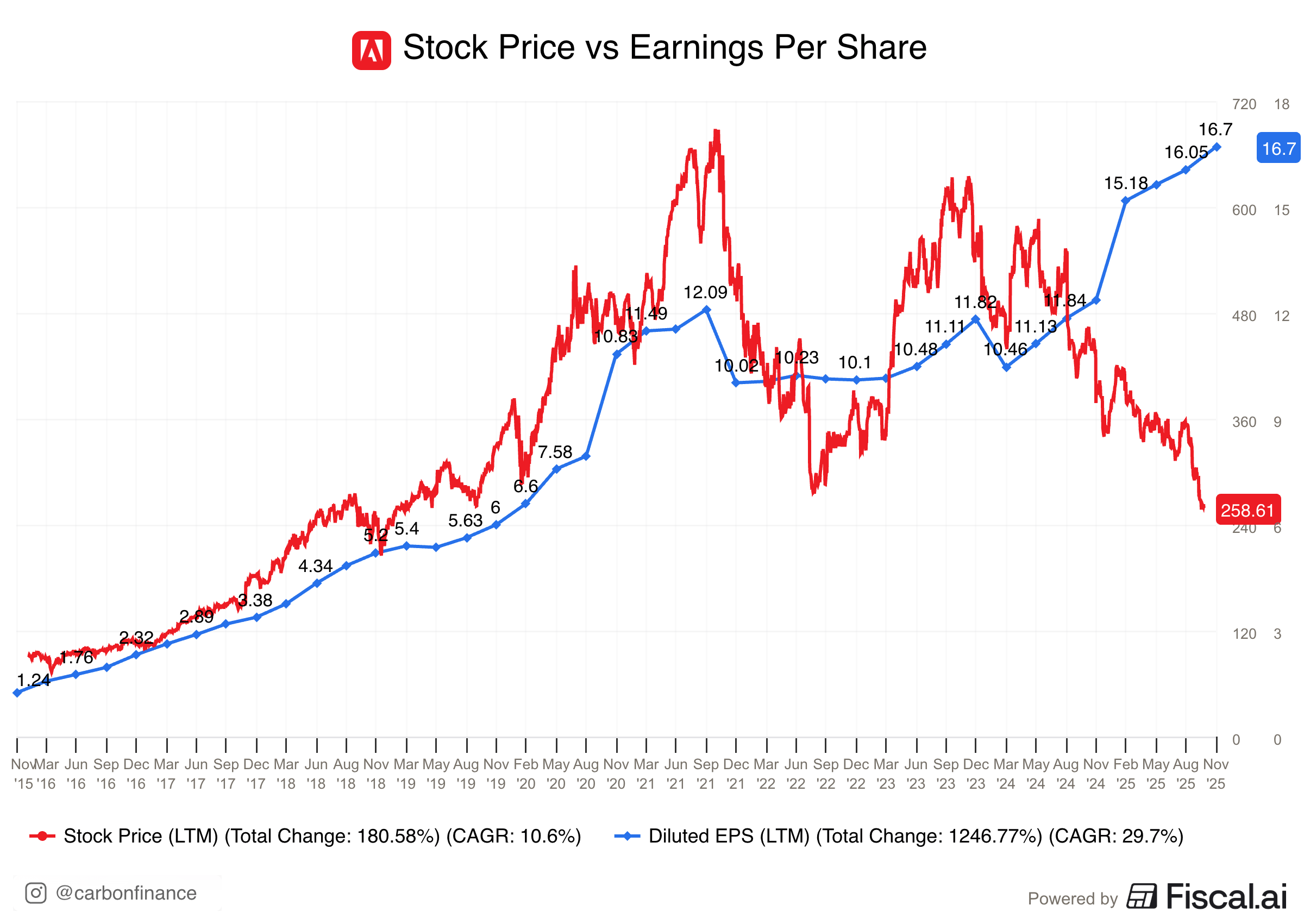

And yet, Adobe’s stock is down over 60% from its all-time high. Market capitalization has plunged from roughly $330B to approximately $105B. This disconnect has less to do with recent execution and more to do with how investors are reassessing Adobe’s future growth prospects and long-term unit economics.

Advancements in generative AI sit at the center of that reassessment. They have altered expectations around how creative work will be produced, who will produce it, and how much software will be required to do so, even if the empirical impact has yet to fully materialize. Layered on top of this shift in perception are several additional sources of uncertainty. Below, I walk through what I view as the most consequential drivers behind Adobe’s recent decline.

1/ Failed Figma Acquisition

Source: Figma

One of the key catalysts behind Adobe’s drawdown was the failed acquisition of Figma.

In September 2022, Adobe announced plans to acquire Figma for $20B. By December 2023, the deal was terminated after regulators signaled there was no viable path to approval, resulting in Adobe paying a $1B breakup fee. From an investor perspective, the failure mattered far more than the fee itself.

Figma represented a workflow Adobe did not own. It was built as a browser-native platform designed for real-time collaboration, aligning naturally with how modern product teams work. Unlike Adobe’s traditional tools, which excel at creating and editing assets, Figma focused on end-to-end product design, bridging interfaces, workflows, and collaboration between design and engineering.

Adobe attempted to compete through Adobe XD, but the effort failed to gain traction. The gap was identity. Adobe’s tools have been built around desktop-first workflows with collaboration layered on later, while Figma was designed for live, multi-user collaboration from inception.

Adobe XD, Source: Adobe

After the acquisition collapsed, Adobe exited the product-design category by sunsetting XD. Adobe effectively conceded a modern, collaborative design workflow at a moment when creative and product workflows were shifting away from desktop-centric creation.

While the direct financial impact was relatively limited, the episode reinforced a broader narrative that Adobe may be slower to adapt organically to new workflow paradigms.

2/ AI-Driven Disruption

AI represents the most consequential long-term uncertainty facing Adobe’s business model. The concern is not a single product or competitor. It is a perceived foundational shift in how creative work is produced and where value accrues across the creative stack.

First, AI lowers the barrier to creation. Tools that rely on prompts rather than craftsmanship allow users to generate acceptable output with little technical expertise. For many students, freelancers, and small businesses, Adobe’s depth increasingly appears optional rather than essential.

Tools like Canva illustrate this dynamic. While they do not meaningfully compete with Adobe at the high end today, they capture users at the very beginning of the creative lifecycle by prioritizing simplicity, collaboration, and speed over depth and control. Their primary audience is not entrenched professionals, but new creators, small teams, and startups that would historically have graduated into Adobe’s ecosystem over time.

In that sense, AI-enabled and web-first tools do not need to displace Adobe at the enterprise level in the near term to matter economically. They only need to alter where users begin. If a growing share of new creators build their habits, workflows, and muscle memory outside of Adobe, the risk is not immediate churn, but a gradual erosion of the future professional funnel.

Source: Canva

Second, AI has introduced a growing expectation that productivity gains will reduce the number of people required to produce content. The market increasingly assumes that if one designer can do the work of several, teams will shrink, and paid seat demand will compress over time.

This expectation has not yet been proven at scale, but it has become embedded in how investors model the future. Even if Adobe retains professional users, the perceived risk is that efficiency gains translate into fewer seats rather than higher spend.

Third, AI introduces a potential monetization mismatch. Adobe’s strategy is banking on higher usage translating into incremental revenue through AI add-ons, credits, or consumption layered on top of subscriptions. That approach only works if usage-driven monetization grows faster than any deceleration in paid seats. If seat counts stagnate or decline faster than incremental consumption ramps, ARPU could remain flat or even compress despite increased engagement.

Adobe’s Generative Credits, Source: Adobe.com

On top of all of this is an even bigger existential fear. As AI becomes more capable, users may increasingly focus on describing outcomes rather than interacting directly with specific tools. If creation shifts from “using software” to “requesting results,” the importance of individual applications could diminish over time, and thus commoditized, even if they remain embedded behind the scenes. This outcome is far from certain, but it highlights the inherent difficulty of predicting how software will be used and valued over the long term.

Taken together, AI has reshaped expectations around entry-point control, seat economics, and long-term monetization, making it a central contributor to Adobe’s re-rating.

3/ Maturity and Slowing Growth

Adobe’s drawdown also reflects maturity. Revenue growth that once eclipsed 20% has since decelerated into the low double digits, where it now appears to be stabilizing.

At Adobe’s scale, the debate is no longer whether the business can grow, but how much growth remains. The company is already deeply embedded across large enterprises. Bloomberg Intelligence estimates that Adobe held roughly 71% share of the global creative software market in 2024, and industry research firms broadly expect this market to grow at a mid-to-high single-digit rate over the coming years. Adobe has also disclosed that 87% of Fortune 100 companies use Adobe Experience Cloud, highlighting the extent of its enterprise penetration.

While Adobe can continue to add new customers, particularly at the entry level and among smaller enterprises, much of the spend that meaningfully moves the needle is already likely captured. As a result, incremental growth must increasingly come from pricing, seat expansion, or higher monetization per user rather than broad-based enterprise adoption. Each of these levers is now being evaluated more critically for the reasons I outlined in the previous section.

This shift in the growth mix matters for valuation. A business compounding at 10% with strong margins and cash generation can still be attractive, but it does not command the same multiple as a company growing at 20% with a long runway ahead. This reframing is yet another reason for the market’s reassessment of Adobe’s valuation.

4/ Regulatory Pressure

Last but not least, Adobe is facing regulatory scrutiny related to its subscription enrollment and cancellation practices.

The direct financial impact appears limited. Adobe has stated that early termination fees represent less than 0.5% of global revenue, meaning their removal would not meaningfully affect earnings directly.

The scope of the case also appears relatively narrow. It largely excludes enterprise customers, who operate under negotiated agreements rather than standardized online plans. Under Adobe’s new reporting, Business Professionals and Consumers account for roughly 29% of subscription revenue. Regulatory exposure is largely confined to Adobe’s smaller customer segment, though its fastest growing.

The more relevant risk is behavioral. If cancellation flows and/or contract structures are simplified, churn could increase. Easier cancellation also lowers the cost of experimentation, making it simpler for users to try competing platforms and leave quickly if alternatives are good enough or cheaper.

5. Stress-Testing The Bear Case

The prior section outlined the major pressure points behind Adobe’s largest drawdown in recent years and framed them from the most adverse angle possible. That framing is intentional. Avoiding permanent capital loss requires being explicit about what “worst case” actually looks like, not what is comfortable to assume.

Warren Buffett has a golden rule: Never lose money.

The purpose of this section is not to flip from bearish to bullish. It is to stress-test the bear case and ask what would have to be true for it to be wrong. The goal is to distinguish between what can be supported by evidence today, what remains uncertain, and where expectations may already embed overly pessimistic assumptions.

I recommend you view this as a cross-examination, not a rebuttal.

1/ Figma and Workflow Containment

The market’s concern following the failed Figma acquisition is that Adobe permanently lost control of modern, collaborative product-design workflows and ceded an important part of the creative stack. That concern is directionally fair. Adobe has effectively exited the UI/UX design category.

The key question is whether this represents a fatal impairment or a bounded loss.

Figma’s core strength lies in product-design workflows for applications and websites. Adobe’s historical strength lies elsewhere: asset creation across images, video, motion, documents, and media production. These operate at different stages of the creative supply chain.

In practice, the two ecosystems often coexist. Creative assets are frequently produced in Adobe tools, moved into Figma for interface design and collaboration, and then sometimes returned to Adobe products for final production and delivery.

That coexistence, however, is not static. Figma continues to expand its feature set in ways that reduce reliance on Adobe tools. Recent additions such as native image-to-vector functionality illustrate an effort to keep more of the creative workflow inside Figma’s environment.

While these capabilities currently lack the depth, precision, and production control required for high-end use cases, they signal a clear intent to narrow the workflow gap over time. Whether and how quickly this materially dissolves coexistence is difficult to forecast, but more than likely to take a long time.

Expanding deeper into UI/UX may also not have fit cleanly within Adobe’s broader strategy. Figma’s workflows are web-first, highly specialized, and oriented around product development rather than content production. Fully integrating such a platform into Creative Cloud would likely have been complex, dilutive, and non-linear.

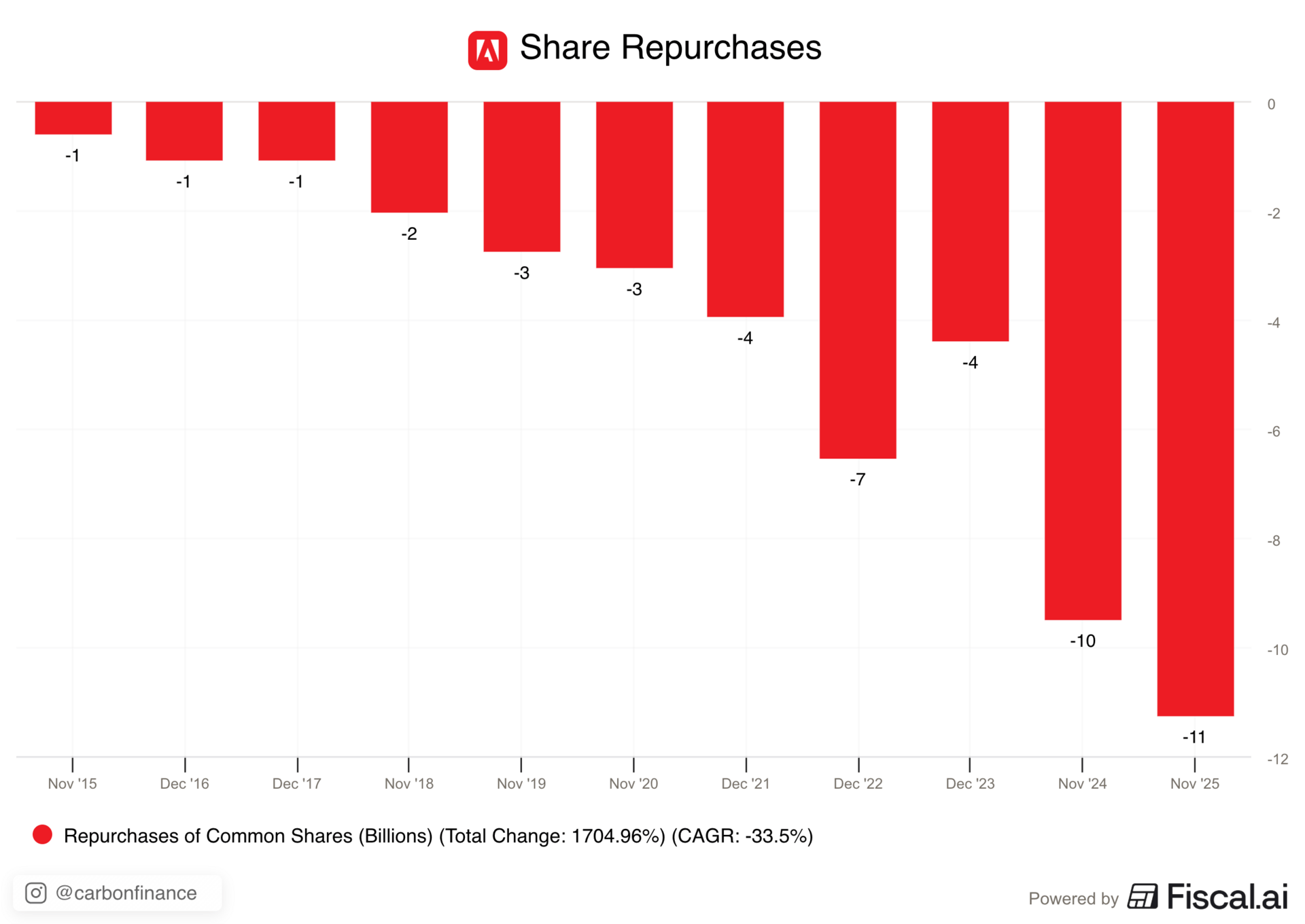

An often overlooked consideration is capital allocation. The proposed deal was structured as roughly 50% cash and 50% stock. By walking away, Adobe avoided diluting shareholders and redeployed capital aggressively into share repurchases. This includes roughly $11B in fiscal 2025 alone, at valuation levels well below historical norms.

Unlike dividends, this approach is tax efficient and mechanically increases per-share ownership and earnings for remaining shareholders without requiring incremental operating improvement. If the share price remains depressed, buybacks alone allow Adobe to become a meaningful share cannibal.

Finally, the deal did not fail due to strategic misalignment or execution. It failed because regulators signaled it would be blocked, an outcome largely outside of Adobe’s control.

It is also worth noting that the market’s reassessment has not been isolated to Adobe. Since its IPO, Figma’s equity value has declined significantly and now trades at a 30% discount to the valuation Adobe originally agreed to pay. While Figma continues to grow, this repricing highlights that investors have broadly compressed multiples across creative software rather than singling out Adobe alone.

Taken together, the failed Figma acquisition exposed a real workflow gap, but the economic damage appears contained. Adobe ceded an adjacent category rather than a core one, retained control and is doubling down on the broader creative supply chain, and avoided deploying substantial capital into a business facing its own long-term disruption risks. This does not eliminate the competitive threat, but it suggests the market may be overstating how existential the loss of Figma truly is.

2/ AI and Competitive Dynamics

The AI bear case on Adobe is straightforward. Many investors expect competitors to capture users at the entry level. Enterprises may eventually need fewer seats and ditch Adobe for alternatives. New tools could weaken pricing power. And over time, Adobe’s role in the creative stack could shrink rather than expand.

Let’s discuss whether the evidence supports that view.

A/ Entry-Point Funnel

AI has undeniably lowered the barriers to content creation. Canva and AI-native tools like Midjourney allow users to generate acceptable output with limited technical expertise. If new creators build habits outside Adobe’s ecosystem, the long-term professional funnel could narrow even without near-term churn.

Entry-point disruption therefore affects future adoption dynamics more than current revenue, and is unlikely to happen rapidly, in my view.

Why? Because Adobe’s response has centered on expanding distribution while reinforcing its position at the entry and enterprise layers of the market.

Adobe Express operates both as a standalone entry product and as an embedded layer within Creative Cloud. It enables non-designers inside enterprise accounts while serving as a funnel for new users who may later shift into higher-value subscriptions.

Source: Adobe

Demand for Express, along with Adobe’s other key entry product Acrobat, remain robust. In the most recent quarter, Acrobat and Express grew 20% YoY to over 750M MAUs. Over 45 new partners were added to the Express ecosystem, and more than 25,000 businesses purchased Express or Acrobat Studio for the first time, accelerating QoQ.

Adobe is also reinforcing early exposure through education. More than 40M K–12 students have access to Adobe Express for Education, and over 100 higher education institutions are designated Adobe Creative Campuses. In Q4, student access to Express Premium grew more than 70% YoY. This sustained exposure reinforces Adobe’s presence at the beginning of the creative lifecycle, which is incredibly important as competition intensifies.

Source: Bloomberg

Financially, Adobe has also aggressively increased advertising spend to approximately $1.4B in fiscal 2025, up more than 30% YoY. At its scale, it has the resources to defend share and acquire early-stage users in a way that smaller competitors may struggle to maintain, especially if AI funding plateaus.

More broadly, Adobe has embedded its capabilities into newer platforms where users already work. Integrations with Microsoft 365, Google Workspace, and ChatGPT position Adobe as a creative layer inside dominant productivity environments rather than a destination application.

Source: Adobe

Together, these initiatives help defend existing users while expanding the upstream funnel. If entry-level adoption through Express, education partnerships, and embedded distribution translates into conversions to higher-tier Creative Cloud subscriptions over time, incremental revenue could follow. That conversion dynamic involves a natural time lag and remains unproven, but it is a variable worth monitoring.

Adobe does not need to eliminate entry-level competition to succeed. It needs enough product depth, integration, and distribution strength to attract and retain consumers and small businesses while preventing coordinated displacement. So far, the data suggests it is doing enough.

B/ Enterprise Durability

Much of the disruption narrative focuses on consumer usage, as that is where upstream risk begins. But Adobe’s financial foundation is anchored in enterprise customers, where switching costs and workflow integration run far deeper. There is no evidence today of large enterprises moving away from Adobe. If anything, those relationships appear to be getting stronger.

Adobe has disclosed that nearly all Fortune 100 companies have used AI features within its applications. 90% of its largest customers have adopted AI-first products such as GenStudio, Firefly Services, or Acrobat AI Assistant. More notably, over 40% of Adobe’s top enterprise customers have doubled their ARR since fiscal 2023.

Competitors would like to fill this gap. Canva and Apple have begun pushing more aggressively into higher-end creative and enterprise-oriented workflows. While these offerings remain narrower than Adobe’s full production stack, they illustrate that competitors are not content to remain at the entry layer.

Source: Apple

However, the enterprise layer is a different beast. Organizations rely on deeply integrated tools tied to compliance, brand governance, asset management, and cross-functional coordination. Replacing that infrastructure is not a simple product swap. It requires planning, procurement, retraining, and system migration that unfold over years rather than quarters.

Additionally, many AI tools like Midjourney and Nano Banana Pro remain output tools rather than workflow systems. They lack the governance, version control, and enterprise integration we just discussed. In other words, they do not pose an infrastructure level threat at their current state.

Adobe’s response to these tools is Firefly. Rather than ignoring generative creation, Adobe embedded it directly into its core tools and enterprise workflows. Since its launch, over 29B images have been generated with Firefly. The tool is available in both lightweight tools like Express as well as more advanced applications like Photoshop. This internalizes the output threat rather than ceding it. Whether that fully neutralizes the risk depends not on feature parity, but on whether users and companies continue to value depth, control, and integration over standalone generation. I firmly believe that will be the case.

Source: Adobe

At the model layer, Adobe integrates third-party AI models alongside its own in Firefly (including Google’s Nano Banana Pro!). Rather than betting on a single proprietary stack, it allows users to access multiple models within one interface. This model orchestration strategy aims to optimize output quality while keeping workflows inside Adobe’s ecosystem. In theory, this reduces the risk of users ditching Adobe to access model innovation elsewhere and offers a superior value proposition compared to only using a single model.

Adobe also benefits from the depth of its commercially safe asset library. With more than 700M Adobe Stock assets and enterprise-safe generative training data, the company offers a legal and compliance framework that many competitors cannot match. For large enterprises, intellectual property risk is not theoretical, and commercially indemnified content remains a strong competitive advantage.

Source: Adobe

Finally, Adobe is focused on turning consumption into creation. Management has stated that much enterprise work begins with existing PDFs, documents, and stored assets. By embedding generative tools directly into those files, Adobe allows users to create new content from existing materials and enhance assets that were already being designed. That expands monetization within products that historically skewed toward consumption, while increasing the friction of moving entire content libraries to another platform.

There is a meaningful difference between experimenting with new tools and replacing core enterprise infrastructure. If erosion were occurring at scale, it would likely appear first in large-account ARR trends. That signal has not emerged. Given the complexity of enterprise migration, combined with Adobe’s continued integration of AI into existing workflows, the cost of moving away appears much higher than the narrative implies.

3/ Growth and Monetization Mechanics

Competitive positioning is one side of the equation. The more important question is economic capture. If AI changes how content is created, how does Adobe get paid?

Adobe is shifting toward usage-linked pricing through generative credits and APIs. Credits function as a usage-based currency. Casual users remain within base allocations under their subscription, while power users purchase incremental credits aligned to rate-card pricing. This structure allows Adobe to tie revenue to usage intensity rather than relying solely on seat growth.

Importantly, Adobe’s scale may provide a structural cost advantage. With broad enterprise penetration and centralized distribution, Adobe can negotiate model access and API pricing at volumes individual users or smaller platforms cannot. In theory, this creates room to capture margin between underlying model costs and enterprise value, particularly as generative functionality becomes embedded across large customer bases.

Adobe Firefly Models, Source: Adobe

Conceptually, the approach makes sense. The challenge is measurement.

Adobe does not disclose seat counts, net seat adds, or detailed credit unit economics. It is therefore unclear whether usage-based monetization can fully offset any future seat compression, or whether productivity gains ultimately reduce labor costs rather than expand software budgets. For the most pessimistic AI scenario to prove correct, sustained seat contraction would need to emerge alongside failure of usage-based monetization to scale. This is an overhang all software companies face today, not just Adobe, and longer-term elasticity remains to be seen.

However, Adobe is not witnessing a collapse in unit economics today. Management addressed seat dilution concerns at Adobe MAX, stating they continue to see Creative Cloud seat growth alongside expanding usage across Express and Firefly. While qualitative, this counters the most aggressive dilution narratives. Additionally, user engagement continues to expand. Total MAUs grew >15% across Acrobat, Creative Cloud, Express, and Firefly, with Creative freemium products growing >35% YoY. More broadly, customers spending >$10M in ARR grew roughly 25% YoY and generative credit consumption tripled sequentially.

Also, the Business Professionals and Consumers segment has grown sales in the mid-teens, demonstrating that entry-level and lighter-weight use cases continue to compound. Enterprise also remains steady.

Now, stepping back. Overall revenue growth has clearly decelerated. After compounding at more than 20% for much of the last decade, growth has stepped down and stabilized in the low double-digit range. This is a reset followed by stabilization, not a collapse, and the pattern is consistent across segments and geographies.

Two explanations plausibly coexist. Competition has increased, which snagged some market share. At the same time, pandemic-era pull-forward likely compressed several years of demand into a shorter window.

What matters is that both entry-level and enterprise indicators remain intact. The data points to a lower but stable growth baseline rather than an accelerating decline. Adobe still has room to expand through new-user acquisition and deeper enterprise integration, though penetration is already high. If usage-based monetization scales, it could support incremental revenue over time. That said, long-term outcomes will depend on seat dynamics, output elasticity, and budget allocation decisions that are not yet observable.

From here, modest deceleration would not be surprising due to Adobe’s size and scale. However, larger cracks in the foundation would require evidence that has not emerged and doesn’t appear likely.

4/ The Scope of Regulatory Impact

Regulatory scrutiny alone is unlikely to break the investment thesis. The direct financial exposure is limited, and the litigation primarily targets consumer plans rather than the enterprise base.

For this issue to materially impact Adobe’s economics, churn within the affected segment would need to rise meaningfully and persistently. That would imply a large base of low-intent or inactive users artificially inflating subscription counts, a dynamic not supported by current engagement trends, as we saw above. Monthly active users across key products continue to expand, which is inconsistent with widespread “zombie” subscriptions.

Overall, regulatory pressure appears incremental rather than structural. It is a risk worth monitoring, but not one that presently alters the core thesis in my view.

6. Valuation

Adobe’s valuation today reads like the market has already written the obituary, even though the business remains stable.

1/ Forward EV/FCF

On a forward EV / free cash flow basis, Adobe trades at just 10.5x.

EV / FCF is useful here because the central debate is about the durability of Adobe’s cash generation. Free cash flow reflects the actual economics available to shareholders, and enterprise value accounts for capital structure, making it a cleaner measure than earnings alone.

Over the past decade, Adobe has traded at an average forward EV / FCF multiple of roughly 27x. At current levels, the stock trades at a 60% discount to that historical norm.

2/ Forward PE

On a forward earnings basis, Adobe trades at just 11x.

Over the past decade, the stock has averaged closer to 31x forward earnings, clearly indicating that today’s multiple reflects a complete reset in future expectations.

For context, the S&P 500 trades at roughly 22x forward earnings. Adobe now trades at half the market multiple despite superior margins, strong cash generation, and a strong balance sheet compared to the average company in the index. Truly a remarkable sight.

3/ Discounted Cash Flow

To estimate intrinsic value, I use a discounted cash flow framework based on free cash flow per share. A per-share lens captures both dilution and capital allocation directly, focusing on the cash ultimately accruing to shareholders.

Historically, Adobe’s free cash flow per share compounded at roughly 25% annually over the last decade. That stepped down to approximately 16% over the last five years and roughly 14% over the last three years.

Forward expectations are more modest. Analyst estimates imply free cash flow growth of roughly 10% in 2026, 9% in 2027, and mid-single digits thereafter. My scenario assumptions lean considerably below long-term historical averages and analyst estimates. They also do do not require heavy multiple expansion.

Across conservative low, base, and high cases, the probability-weighted intrinsic value approximates $394 per share. At a current price of $259, the stock trades at roughly a 34% discount to that estimate. Something that caught my eye? Even in my worst-case scenario, which assumes low single-digit growth and a restrained terminal multiple, the estimated intrinsic value is still above today’s price.

What does this all mean? At today’s price, the market is effectively assuming little to no long-term growth in per-share cash flow. The DCF suggests that even modest growth across conservative scenarios supports materially higher value without relying on aggressive assumptions or significant multiple expansion. If my growth assumptions prove correct, the current price today implies mid-double-digit annualized returns.

7. Final Take

There is a clear disconnect between narrative and valuation.

Adobe is being priced as though its long-term economics have already deteriorated. Yet the business continues to grow, generate significant cash, and deepen its enterprise relationships. What has collapsed is not the financial model, but confidence in the broader SaaS framework in an AI-driven world.

The stock deserved a re-rating. It traded at a premium multiple for years. But the pendulum appears to have swung too far. At current levels, investors do not need re-acceleration or category dominance for this to work. Adobe simply needs to continue growing modestly, maintain cash generation, and avoid a breakdown in its core workflows. That bar is lower than the market is currently implying.

As I’ve already emphasized, the real uncertainty lies in AI monetization. It is difficult to forecast how usage-based pricing, generative credits, and evolving seat dynamics ultimately settle. Management has not yet provided enough transparency to fully model the economics, and that ambiguity is uncomfortable. That is part of the reason the stock has fallen to current levels. Some investors will avoid Adobe for that reason and I completely understand it. The unit economics are harder to forecast than they were five years ago.

But at under $260 a share, the setup is asymmetric. The valuation already embeds prolonged stagnation. If Adobe can grow in the high single digits and continue aggressively repurchasing shares, the downside appears limited relative to the potential normalization in sentiment and multiple.

Importantly, this is not an unknowable situation. There are clear metrics that management can share that will signal whether the thesis is working or breaking, from AI-first revenue and credit monetization to seat trends and enterprise expansion. Greater transparency would make the trajectory far easier to assess.

From my perspective, this is not a bet on perfection. It is a bet that Adobe remains economically relevant and that the market’s current assumptions are too severe. I am initiating a small position and would welcome further weakness toward the low $230s, provided any decline is driven by volatility or short-term noise rather than a change in the underlying fundamentals. At those levels, long-term support converges and buybacks become even more accretive.

Adobe does not need to win the AI race outright. It simply needs to survive and compound. At today’s price and based on recent growth rates, that is a reasonable bet.

Disclaimer

I hold a position in $ADBE.

This report is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, legal, or other professional advice. The content provided herein is based on publicly available information and independent research at the time of publication and may not be accurate, complete, or up-to-date. No guarantees are made regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information or analysis provided.

Any opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the opinions or views of any past, present, or future employers. The author is not a licensed financial advisor, broker-dealer, or tax professional. Readers are strongly advised to conduct their own due diligence and consult with qualified professionals before making any financial, investment, or legal decisions.

You should assume that, as of the publication date of this report or any communication referencing publicly traded securities or assets, the author may have a position in the securities or assets mentioned and may stand to realize significant gains if the price moves. Following publication, the author may continue transacting in the securities discussed and may be long, short, or neutral at any time thereafter, regardless of the initial position. The author reserves the right to alter any position at any time without notice.

There is no obligation to update any information after publication. The author and affiliated parties are not responsible for any changes in market conditions, economic shifts, or new developments that may impact the accuracy of the content.

Forward-Looking Statements

This report may contain forward-looking statements, including but not limited to projections, estimates, and expectations regarding financial performance, market trends, and future company developments. These statements are based on assumptions that may prove incorrect, and actual results may differ materially. The author assumes no responsibility for updating forward-looking statements in light of new information or future events.

Third-Party Data & External Sources

This report may rely on data from third-party sources believed to be reliable. However, the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of such data cannot be guaranteed. The author assumes no liability for errors, omissions, or inaccuracies in third-party data and does not endorse or take responsibility for the methodologies used by these external sources.

AI-Generated Enhancements

This report was optimized using AI for clarity, structure, and conciseness. AI tools also assisted in research organization, idea generation, and analytical stress testing. All analysis, conclusions, and opinions remain the author’s own.

Confidentiality & Redistribution

Readers are welcome to share this report with others; however, copying, reproducing, republishing, or modifying its content in any form without prior written permission is strictly prohibited.

Investment Risk Disclosure

Investing involves risks, including the loss of principal. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The mention of any securities, companies, or investment strategies does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation. Any reliance placed on the information in this report is strictly at the reader’s own risk.

The author and affiliated parties shall not be held liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, or other damages arising out of the use of this report or any reliance on the information provided. By accessing this report, you agree to indemnify and hold harmless the author and affiliated parties from any claims, liabilities, or damages resulting from your use of the content.

You are solely responsible for your own decisions. Proceed at your own risk.

Reply